Guest post from Mark Pasamaneck, PE

In this article, I will explore the relationship between the engineeringdesign process and the failure of a plumbing component as it

relates to product liability.

In the litigious society in which we live, everyone connected to

the life-cycle of a plumbing component should be concerned with

its long-term suitability as it exists in any plumbing system. As an

engineer or designer of a plumbing component, you should have

a desire to go beyond just limiting liability. As described in the

codes and most engineering ethics documents, a designer must be

concerned with protecting the people and property exposed to his

design from seen or unseen damage and hazards.

A LITLE HISTORY

A LITLE HISTORY

While the political, social, and legal reasons are beyond the

scope of this article, the decade of the 1970s was largely considered

the decade of safety awareness. While a few federal

acts were aimed at safety in the 1950s, the majority of the

safety acts in use today were developed in the late 1960s and

first published in the 1970s, including the Consumer Product

Safety Act of 1972. The Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act of 1975

gave broad powers to the Federal Trade Commission regarding

product warranties.

Of particular interest to the plumbing community is that

the majority of the plumbing components in use today were

conceived of and designed well before the 1970s. Many manufacturers

have never evaluated their components or designs in

light of the safety acts and standards implemented in the 1970s

and after. While the building codes commonly grandfather in

outdated technologies, there is no such provision for an old

product design that was produced in the modern era. It is also

obvious that courts have held that the “product” for which a

designer or producer is responsible includes such items as the

warranty, instructions, packaging, labels, and warnings (note:

not an all-inclusive list).

THE ENGINERING DESIGN PROCESS

While the topic of engineering design in general would take many

articles, this discussion on product liability requires an overview of

the engineering design process. The design process commonly is

called iterative since it is very rare that an idea can go through the

steps of concept to finished product without changes. The design

process outlined below is considered the standard in all types of

industry. While many more steps may be encountered in a complex

part or system, the following serves to define the general steps

useful in the design iteration. This process also incorporates the

cradle-to-grave responsibility of the designer and manufacturer.

1. Define the function of the product within a system or as a

stand alone.

• If the product is itself a system, define each subsystem and

initiate an independent design iteration until each component

is uniquely defined.

• If the product is within a system, define system parameters

and environments in which the product will operate.

2. Identify prior designs that may assist or preclude (patents)

the design process.

3. Identify all laws, codes, or standards that apply to

the product or system.

4. Brainstorm possible design concepts.

5. Remove concepts that are not viable due to manufacturability,

regulations, cost, hazards, complexity, integration,

functionality, or aesthetics.

6. Choose a design concept.

7. Create the design using accepted design practices applicable

to the field of interest. These will necessarily include

factors of safety, dynamic loads, static loads, wear, compatibility,

environment of use, durability, cost issues, and

materials (suitability, durability, strength, degradation,

fabrication, identification of failure modes, and predictable

failure locations).

8. Evaluate functionality: geometry, motion, size, complexity,

and ergonomics.

9. Evaluate safety: operational, human, environmental, and

failure analysis.

10. Evaluate energy: requirements, created, kinematic, thermodynamic,

and chemical.

11. Evaluate quality: marketability, longevity, aesthetics, and

durability.

12. Evaluate manufacturability: available processes and new

processes.

13. Evaluate environmental aspects: materials, fluids,

wastes, interactions, phase changes, flammability,

and toxicology.

14. Iterate the design. (Redo steps 7 through 13 based on

the analysis.)

15. Lay out the design.

16. Obtain manufacturing criteria.

17. Create a prototype and test (optional).

18. Create the product.

19. Test the product.

20. Reiterate through the entire design process based on

testing and analysis.

21. Produce the product. Some changes may occur, but they

should not impact the actual design.

22. Perform quality control, which is used to evaluate the

compliance of the produced product with the design.

23. Deliver the product. Packaging, labeling, instructions,

and warnings are included in this step, but they also

must be considered throughout the process.

24. Consumers use the product. The producer must consider

the environment of intended use as well as anticipated or

probable misuse of the product. These must be addressed

appropriately throughout the design process.

25. Dispose of product. The end of use must be considered

by the designers. Fail-safe designs should be incorporated,

and any hazards associated with disposal and/or failure

must be addressed appropriately as well.

SAFETY HIERARCHY

Steps 7, 8, 9, and 19 are where a defect or hazard (such as that

shown in Figure 1) should be detected in most cases. When

detected, the question must be answered as to whether the

defect or hazard was foreseeable or unreasonably dangerous.

If it was, the commonly held approach in the engineering community

to solve the problem is known as the safety hierarchy.

This process is based on sound engineering principles coupled

with economic considerations and human factors. The first

reasonable item in the hierarchy must be utilized, and skipping

steps is not appropriate.

The steps are as follows:

1. Design it out.

2. Guard it out.

3. Train it out.

4. Warn it out.

5. Don’t make it.

The hierarchy is intended to evaluate if the problem can be

corrected by engineering measures. However, those measures

also can be evaluated in and of themselves. For example, were the

warnings understandable, sufficiently broad, or used as a substitute

for design or guarding?

The design process and the safety hierarchy outlined above

almost always include other sub-processes and evaluation techniques.

Severity indices, fault trees, failure mode and effect analysis

(FMEA), root cause analysis, and design checklists all are tools

that if sufficiently designed and used within the design process

will aid the designer in his goal to make a safer product.

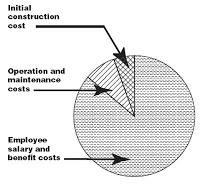

PRODUCT LIABILITY THEORIES

When product liability theories are evaluated, three general areas

are considered.

1. Design defect:

• Was the product designed to do the job based on the reasonable

expectation of a consumer, without undue risk?

• Was it designed for the environment of intended use?

• Was the design properly engineered and tested?

2. Manufacturing defect: Despite a sufficient design, was there a

flaw in the:

• Processing?

• Assembly?

• Raw materials?

3. Warning defect: Did the manufacturer fail to properly advise

regarding:

• Assembly?

• Use and maintenance?

• Hazards?

AVOIDING LIABILITY

Hopefully, if you have made it this far, you now are asking yourself

how you can improve your products to both reduce liability and

improve safety. Much of the general information on design is

contained herein, but a more in-depth understanding obviously

would be beneficial for the designer.

Let’s look at design defects first. It is important to document

what sources of information were used or considered in the design

process of a component. The specific issues for the plumbing component

designer that account for a large number of design-related

defects are related to stress concentrations and material selection.

ASPE publishes the Plumbing Engineering Design Handbook,

and Volume 4 covers plumbing components and equipment. I

have utilized this reference for years to illustrate what a designer

“should” have included in a design. While a lot of good information

is available online, if you use it in a design, be sure to properly

record and document the source. Materials, machinery, and

design handbooks are prevalent and should be sourced for relevant

design information. One of the various texts on design and

product liability (see Figure 2) also should be included. One of the

best for a general understanding is Managing Engineering Design

by Hales and Gooch.

Manufacturing defects come in two main areas: assembly

and cast/mold defects. This is an area that the designer typically

cannot control, but can influence. Some issues of quality control

and tolerances have to be determined within the design, and

others will be left to the assembly workers, a quality control (QC)

department, or line design. When it comes to casting and mold

defects, those processes should be considered and properly speci-

fied in the design. Then a QC program to ensure compliance must

be implemented (see Figure 3).

The third area is related to warnings. Step 3 of the safety hierarchy

would be evaluated in this step as instructions for installation

and maintenance (training). It is the responsibility of the

design engineer and producing company to ensure that a product

brought to market is reasonably safe and suitable for the environment

of its intended use. A product subject to degradation,

corrosion, catastrophic failure, or other risk of damage to people

or property should adequately warn of the risk or danger if there

was no other reasonable way to eliminate the risk or failure mode.

The product instructions might address, but not be limited to,

warnings, providing maintenance instructions, and warning of the

consequences of failing to heed the instructions.

The design of warnings should follow American National Standards

Institute (ANSI) standards regarding the identification and

warning against potential safety hazards. In 1979, the ANSI Z53

Committee of Safety Colors was combined with the Z35 Committee

on Safety Signs to form the Z535 Committee, which develops

the standards that must be used to design warnings, labels, and

instructions intended to identify and warn against hazards and

prevent accidents. The relevant standards for products are:

• ANSI Z535.4:

Product Safety Signs and Labels

• ANSI Z535.6:

Product Safety Information in Product Manuals,

Instructions, and Other Collateral Materials

For a warning to be effective, there must be a reasonable degree

of certainty that the end user will receive and understand the

warning (see Figure 4). The use of warnings also must follow the

safety hierarchy. Since warnings are the fourth step, available

design alternatives must be considered in the design process.

Guarding out of a hazard and subsequent training must be undertaken

before warnings can reasonably be considered or designed.

Our society, as stated in the various plumbing codes, relies on

the engineer, designer, and manufacturer to produce products that

are safe and durable. Society also recognizes and accepts some

level of risk, provided that they know about it beforehand and that

companies must be economically viable to survive. Don’t shirk your

responsibility to the public, your profession, yourself, or your company

by producing a product based on an insufficient design.

This article was reprinted with permission and all copyright remains with the American Society of Plumbing Engineers.