This is an encore of an article Michael Chusid wrote almost 20 years ago. Since then, the construction industry has been increasingly globalized. However, most of their observations about the North American market remain the same.

Hardie saw a previous recession as a great time to invest in a new market -- a potential that also exists in our current economic malaise. The firm has sold off its gypsum board and irrigation interests, but has established a solid brand and market leadership in the fiberboard category.

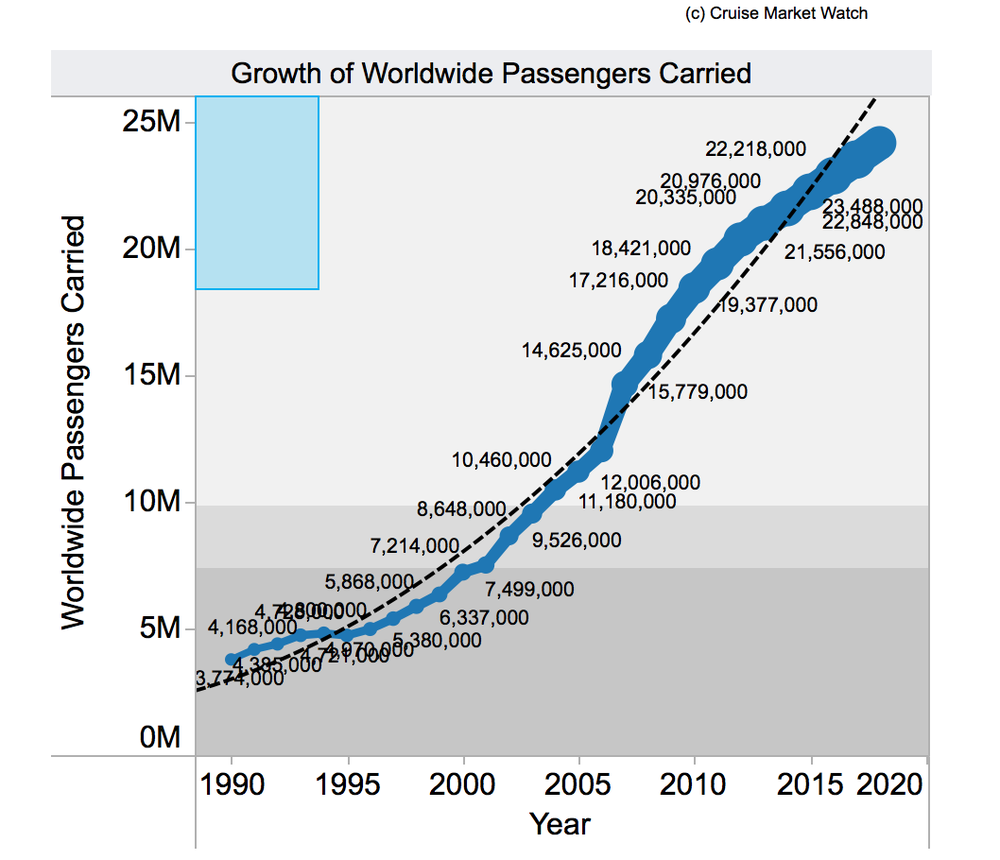

There is good news about the U.S. construction products industry: We enjoy a productive and flexible work force and an excellent safety record. Our designers are open to new products and techniques. We are adventurous, ambitious, and independent. And,

despite the recession, our economic prospects are robust enough to merit substantial investment.

That is the decidedly upbeat view as seen from Australia, home of James Hardie Industries Ltd., whose U.S. subsidiary is rapidly becoming a major player in the North American construction products industry. In just five years, Hardie has become a significant supplier here of gypsum board and a range of fiber-cement products. The company has quickly earned a reputation for quality products and efficient production. Sales at its U.S. unit, which also markets irrigation products and sprinkler fittings grew 21% to $145 million (US) in the fiscal year ending in March.

Hardie's trek into the U. S, market has not been without a few bumps, however. Hurt by the construction downturn and severe price-cutting in the gypsum market, the U.S. unit lost $14.5 million last year. The company has had a tough time, especially at first, getting U.S

. contractors to try its high-cost fiber-cement products. And it took a few missteps to make Hardie realize it had to Americanize its marketing operations to be successful here.

Things are just now beginning to shape up. Don Manson, president of the Mission Viejo, CA-headquartered unit, says both sales and profits improved "significantly" in the first half of this year, thanks mostly to growth in the fiber-cement business. "I'll be very surprised if we're not profitable in fiscal 1994," Manson says.

If so, the U.S. unit will be on its way to following in the rather large footsteps of its Sydney-based parent, one of Australia's leading industrial manufacturers and a dominant producer of cladding there. For most of James Hardie's 100-year history, the company's chief product had been asbestos-cement board, popular in Australia's hot, humid coastal cities. But when health concerns about asbestos surfaced, Hardie switched in 1980 to a wood-fiber cement board. It retains most of asbestos' desirable properties, but it is stronger and easier to work with.

Coming to America

About that same time, the company began to diversify through a series of acquisitions and product developments. It grew into a billion-dollar company, but its development was limited by the size of its home markets of Australia aid New Zealand, whose combined population of 20 million is less than California's.

"The question then was,

do we expand into other activities or do we take our knowledge to other parts of the world? We chose to do the latter," says Manson, formerly head of Hardie's New Zealand unit. "We had extremely good products and technology, so it was a question of how to capitalize on it. We looked to the United States because we saw somewhat similar building practices, an extremely large population, and a relatively common language."

Another factor was the mid-1980s collapse of Johns Manville, a leading U.S. supplier of asbestos-cement products. "We saw a vacuum here for [non-asbestos] cement panels," says Pat Collins, technical services manager for Hardie's U.S. building products division. Also, the U.S. market was not entirely new to Hardie. The company had already made inroads by bringing in its irrigation and sprinkler products in the 1970s.

Hardie's expansion into the United States began in earnest in 1987. That year Hardie bought a gypsum quarry and a gypsum board plant in Las Vegas and another plant in Seattle. It also began exporting some fiber-cement products to the United States, though by 1990, it was making those products at its Fontana, CA plant.

At first, the company combined the gypsum and fiber-cement operations, but it later reorganized them into two divisions. "They are separate businesses," Manson explains.

While gypsum board is a price-sensitive commodity product, the high cost fiber-cement products are more proprietary and require missionary work to sell. And while Hardie's gypsum boards are marketed on the West Coast and exported to countries such as Korea, the fiber cement products are sold in the Sun Belt.

The company makes three types of fiber-cement products: siding, backer hoard, and roofing shingles. They are sold mostly in niche residential markets where their unique properties can be marketed at a higher cost. The backer board has shown the most market growth and potential. It can command a small premium because it provides the smooth finish necessary with vinyl flooring, and its water impermeability makes it ideal behind ceramic tiles in wet areas.

The roofing shingle has had a relatively high penetration in California, but Hardie won't be able to expand the market North until it perfects the shingle's freeze/thaw properties. The siding, which has had slow growth, has faced tough competition from other cladding, mostly wood, because of cost and aesthetic reasons.

Its main selling point is its long life, and that's not as much of a concern in the United States as in Australia.

Though the Fontana plant is now running at only half its 100,000 tons per-year capacity, Hardie sees enough market potential to warrant buying land near Tampa, FL for a second fiber cement plant.

Hardie has met with some frustrations, though. It has had difficulty getting U.S. contractors to get past their low-cost mentality and try Hardie's fiber-cement products. "The acceptance has taken a little longer than we anticipated," Manson says. "Even though our product may be clearly superior,

if the tradesman has been used to doing things a certain way for 20 to 30 years, he's not going to change quickly.

"It has taken until this year. But now it's really coming on." U.S. sales of Hardie's fiber-cement products grew 14% in fiscal 1992 and that division cut its losses 15%. "And that's being achieved against a depressed economy," Manson says.

Fitting in

Hardie's initial projections underestimated the U.S. demand for fiber cement shingles, mainly because shingles are not popular in Australia. Such

predisposed outlooks are one of the hazards of transporting a business from one country to another. Despite their similarities, Australia and the United States have much different marketing environments.

"

It's taken five years to come to terms with and fit into American culture," Collin says. "The slowness in getting to that stage was due to Australian attitudes and traditions trying to be imposed onto American culture. It doesn't work.

We had to become an American company run by Americans."

And that is exactly what Hardie became. The building products division, for example, is now run by an American, vice president and general manager Louis Gries, and a management team recruited from U.S. firms. Collins is one of the few Australian expatriates still in the United States. Both he and Manson, a New Zealander, see their roles as transitional and temporary.

One adjustment Hardie made after a few years in the U.S. market was to decentralize its marketing organization by putting senior staff in regional offices, rather than have them manage from afar. "That's made a powerful difference," Manson says.

As Collins explains it, a decentralized structure is not a necessity in the smaller Australia. But in the United States, it's a must. "

This country is so large that we can't talk about just one country from a marketing or manufacturing point of view," he says. "In each place it has to be carefully done to fit the local requirements and culture. It's 50 different countries really."

Another difference Manson has observed in the U.S. market is its cavalier attitude towards quality. Australians, by contrast, are a less mobile people and tend to use higher quality building materials to build homes for a lifetime. "It surprised me that the expectations of consumers are not great here," he says. "

I see enormous homes with high prices, but the quality is not dramatic.

"Our backer board is an excellent product, but it gets covered by tile and is out of sight. It's hard for the builder to justify an additional cost. How do you [charge a premium] when it's coming out of the builder's profits?'

The answer, says Mike Going, Hardie's U.S. marketing manager until his recent return to the New Zealand unit, is aggressive marketing that will convince contractors and home buyers that quality is worth the extra cost. "Hardie must

foster an aggressive and creative marketing vision while at the same time doing all the small things that have to be done to carry out a successful marketing program."

Have a question you'd like us to answer?

Send an email to

michaelchusid@chusid.com

By Michael Chusid, Originally published in Construction Marketing Today, ©1992