This is an encore of an article by Michael Chusid that was first published over a decade ago. The specific examples cited are no longer accurate, but the principles remain the same.

An awareness of building product trends can contribute to an architect's ability to stay in the forefront of design and technology. The marketing concept of "product life cycle" provides a useful tool for this. By evaluating where a product is in its life cycle, an architect can anticipate changes in its availability, recognize new channels of promotion and distribution, assess the risks associated with its use, and make sense of the rapid evolution and introduction of new products.

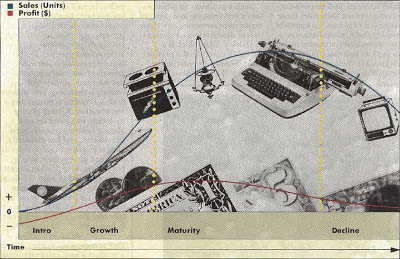

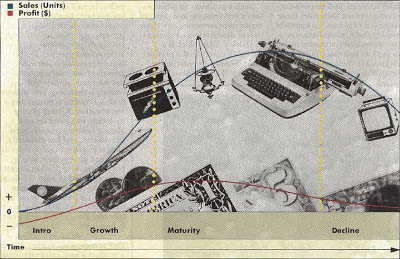

Product life cycles are typically divided into four phases based on sales performance, and form a characteristic "S"-shaped curve. The introduction of a new product is marked by slow sales growth. It takes time to train salesmen, build distribution channels, overcome reluctance to change established behavioral patterns, and get the new product into the specification pipeline. Manufacturers must identify innovative customers and work closely with them during this phase to persuade them to give the product a trial. Because of heavy start-up costs and promotional requirements, little or no profit is realized by a manufacturer during this phase, despite typically high prices. Intelligent building systems are in this introductory phase.

Product life cycles are typically divided into four phases based on sales performance, and form a characteristic "S"-shaped curve. The introduction of a new product is marked by slow sales growth. It takes time to train salesmen, build distribution channels, overcome reluctance to change established behavioral patterns, and get the new product into the specification pipeline. Manufacturers must identify innovative customers and work closely with them during this phase to persuade them to give the product a trial. Because of heavy start-up costs and promotional requirements, little or no profit is realized by a manufacturer during this phase, despite typically high prices. Intelligent building systems are in this introductory phase.

During the growth phase, a product obtains rapid market acceptance and improved profitability. "Where has the product been used?" is a question architects often ask, and in this phase the majority of firms will follow the lead of the early-users. Increased demand will stimulate competitors to introduce new product options. Although manufacturers continue to provide high levels of promotion, prices tend to remain stable, while profitability increases as the cost per sale drops and the economies of production increase. Exterior insulation and finish systems are in such a growth phase.

Mature products are marked by a slowdown in sales growth and profitability. Market saturation occurs when the product has been accepted by most of its potential buyers. Sales volume is affected more by the level of construction activity than by sales activities, and manufacturers may reduce their sales force to control expenses. To maintain market share, manufacturers cut prices, look for market niches to exploit, and make other modifications to their product or marketing mix. Most building products are mature, and basic materials such as gypsum board are "commodity" products with little or no difference among manufacturers' products.

As a product starts to decline, sales and profits erode. Architectural porcelain on steel was once a popular material for service stations and curtain walls, but faced with changing tastes and improved organic coating systems, demand for the product has declined dramatically.

Such a product can often obtain a rejuvenation as a result of major improvements, new channels of distribution, or changes in fashion. Glass block is a dramatic example of a product repositioning. Popular in the 1930's and 1940's, glass block declined in sales as insulated glass and fluorescent lighting gained in popularity. The last U.S. manufacturer was ready to close its plant, but recognizing that a new generation of designers was finding new aesthetic and functional uses for glass block, the company repositioned the product and dramatically increased sales.

Within many product categories, various items may be at different phases of their life cycles. In roofing, for example, low-pitched, standing seam metal roofs are no longer limited to pre-engineered metal buildings, but are being introduced as an architectural product. Modified bitumen roofing is still in a growth phase, single ply roofing has matured, asphalt built-up roofing is declining, and coal-tar built-up roofing is attempting a rejuvenation. Among glazing materials, fire-rated ceramic glazing has only recently been introduced, and low-emissivity glass is growing in sales. Sales of insulated glass remain strong, but it is a mature product since it is already used in most building types and climates. And plain float glass is declining in use as tempered, laminated, and other specialty glasses have seen a rise in popularity.

Product life cycles also influence specification writing. When a product is new, extra care must be taken when investigating it for a particular project. Performance or descriptive specifications are appropriate at this stage to clarify exactly what is required. During a product's growth phase, proprietary specifications can be used because advertising will have built widespread awareness of it. And since the product's initial success will frequently have encouraged competitors, "or equal" specifications become feasible. As a product matures, industry standards typically emerge, allowing the use of reference specifications. As a product declines, brand loyalty deteriorates and the product becomes increasingly prone to substitutions.

The rate at which building products are introduced and the speed with which they grow, mature, and decline continues to increase. Building products do not cycle as quickly as many types of consumer goods or high tech industrial products like electronics. Still, almost every category of building materials goes through a complete cycle several times during an architect's career. In many instances, the pace is even faster. As recently as two years ago, for example, high performance water repellents based on silane and siloxane were still in their introductory phase. Only a few brands were available, the price was relatively high, and distribution was often limited to qualified applicators. Heavy sales promotion was required to differentiate the product from acrylic sealers and other pre-existing types of water repellents, and to interest innovative specifiers likely to give the product a trial.

Since then, the silane and siloxane water-repellent market has changed so rapidly that it appears to be entering its mature phase. A key factor in this has been the publication of a federally financed research report establishing criteria for water repellents. This test demonstrated the effectiveness of silane and siloxane water repellents, stimulating increased demand and a proliferation of manufacturers and private brand labels. As competition increased, prices fell and suppliers shifted their emphasis from promotion to cost-efficient distribution. Brands now struggle against each other to create niche markets and other competitive advantages, and mergers and other forms of market consolidation are occurring. Meanwhile, research and development continues on new types of water-repellent chemistry. While silane and siloxane products may not decline for a number of years, I would not be surprised if a new product type starts the cycle over again in the very near future.

Have a question you'd like us to answer?

Send an email to michaelchusid@chusid.com

By Michael Chusid

Originally published in Progressive Architecture, © 1989

An awareness of building product trends can contribute to an architect's ability to stay in the forefront of design and technology. The marketing concept of "product life cycle" provides a useful tool for this. By evaluating where a product is in its life cycle, an architect can anticipate changes in its availability, recognize new channels of promotion and distribution, assess the risks associated with its use, and make sense of the rapid evolution and introduction of new products.

Product life cycles are typically divided into four phases based on sales performance, and form a characteristic "S"-shaped curve. The introduction of a new product is marked by slow sales growth. It takes time to train salesmen, build distribution channels, overcome reluctance to change established behavioral patterns, and get the new product into the specification pipeline. Manufacturers must identify innovative customers and work closely with them during this phase to persuade them to give the product a trial. Because of heavy start-up costs and promotional requirements, little or no profit is realized by a manufacturer during this phase, despite typically high prices. Intelligent building systems are in this introductory phase.

Product life cycles are typically divided into four phases based on sales performance, and form a characteristic "S"-shaped curve. The introduction of a new product is marked by slow sales growth. It takes time to train salesmen, build distribution channels, overcome reluctance to change established behavioral patterns, and get the new product into the specification pipeline. Manufacturers must identify innovative customers and work closely with them during this phase to persuade them to give the product a trial. Because of heavy start-up costs and promotional requirements, little or no profit is realized by a manufacturer during this phase, despite typically high prices. Intelligent building systems are in this introductory phase.During the growth phase, a product obtains rapid market acceptance and improved profitability. "Where has the product been used?" is a question architects often ask, and in this phase the majority of firms will follow the lead of the early-users. Increased demand will stimulate competitors to introduce new product options. Although manufacturers continue to provide high levels of promotion, prices tend to remain stable, while profitability increases as the cost per sale drops and the economies of production increase. Exterior insulation and finish systems are in such a growth phase.

Mature products are marked by a slowdown in sales growth and profitability. Market saturation occurs when the product has been accepted by most of its potential buyers. Sales volume is affected more by the level of construction activity than by sales activities, and manufacturers may reduce their sales force to control expenses. To maintain market share, manufacturers cut prices, look for market niches to exploit, and make other modifications to their product or marketing mix. Most building products are mature, and basic materials such as gypsum board are "commodity" products with little or no difference among manufacturers' products.

As a product starts to decline, sales and profits erode. Architectural porcelain on steel was once a popular material for service stations and curtain walls, but faced with changing tastes and improved organic coating systems, demand for the product has declined dramatically.

Such a product can often obtain a rejuvenation as a result of major improvements, new channels of distribution, or changes in fashion. Glass block is a dramatic example of a product repositioning. Popular in the 1930's and 1940's, glass block declined in sales as insulated glass and fluorescent lighting gained in popularity. The last U.S. manufacturer was ready to close its plant, but recognizing that a new generation of designers was finding new aesthetic and functional uses for glass block, the company repositioned the product and dramatically increased sales.

Within many product categories, various items may be at different phases of their life cycles. In roofing, for example, low-pitched, standing seam metal roofs are no longer limited to pre-engineered metal buildings, but are being introduced as an architectural product. Modified bitumen roofing is still in a growth phase, single ply roofing has matured, asphalt built-up roofing is declining, and coal-tar built-up roofing is attempting a rejuvenation. Among glazing materials, fire-rated ceramic glazing has only recently been introduced, and low-emissivity glass is growing in sales. Sales of insulated glass remain strong, but it is a mature product since it is already used in most building types and climates. And plain float glass is declining in use as tempered, laminated, and other specialty glasses have seen a rise in popularity.

Product life cycles also influence specification writing. When a product is new, extra care must be taken when investigating it for a particular project. Performance or descriptive specifications are appropriate at this stage to clarify exactly what is required. During a product's growth phase, proprietary specifications can be used because advertising will have built widespread awareness of it. And since the product's initial success will frequently have encouraged competitors, "or equal" specifications become feasible. As a product matures, industry standards typically emerge, allowing the use of reference specifications. As a product declines, brand loyalty deteriorates and the product becomes increasingly prone to substitutions.

The rate at which building products are introduced and the speed with which they grow, mature, and decline continues to increase. Building products do not cycle as quickly as many types of consumer goods or high tech industrial products like electronics. Still, almost every category of building materials goes through a complete cycle several times during an architect's career. In many instances, the pace is even faster. As recently as two years ago, for example, high performance water repellents based on silane and siloxane were still in their introductory phase. Only a few brands were available, the price was relatively high, and distribution was often limited to qualified applicators. Heavy sales promotion was required to differentiate the product from acrylic sealers and other pre-existing types of water repellents, and to interest innovative specifiers likely to give the product a trial.

Since then, the silane and siloxane water-repellent market has changed so rapidly that it appears to be entering its mature phase. A key factor in this has been the publication of a federally financed research report establishing criteria for water repellents. This test demonstrated the effectiveness of silane and siloxane water repellents, stimulating increased demand and a proliferation of manufacturers and private brand labels. As competition increased, prices fell and suppliers shifted their emphasis from promotion to cost-efficient distribution. Brands now struggle against each other to create niche markets and other competitive advantages, and mergers and other forms of market consolidation are occurring. Meanwhile, research and development continues on new types of water-repellent chemistry. While silane and siloxane products may not decline for a number of years, I would not be surprised if a new product type starts the cycle over again in the very near future.

Have a question you'd like us to answer?

Send an email to michaelchusid@chusid.com

By Michael Chusid

Originally published in Progressive Architecture, © 1989