Here's a look at some of the best building products from 15 years ago. See which of these products are still in use and become inspired to see what you can do to make your products last the next 15 years and beyond.

A new curve

A standard tactic in consumer product marketing is to create a brand extension by introducing, for example, a lemon-scented version of a product. Often construction materials makers similarly add a new twist to an existing product. During the past few years, many manufacturers have introduced flexible, bendable, or curved versions of their flat or straight building materials.

Nominees in this category include:

- a new grade of gypsum board specifically designed to bend around curved walls;

- plastic substitutes for lumber that provide flexible wood-like moldings, which can be bent around arched windows;

- Corian’s sheet product, formerly promoted as a flat counter top material, which can now be thermal-formed to create radii;

- and a special crimping process that can put bends in corrugated metal building panels.

And the winner is … concrete blocks for curved walls. The concrete masonry units have the familiar 8"x16" face on one side to match conventional units in adjacent flat walls. But instead of perpendicular ends, the blocks have interlocking male and female joints that can be splayed to form curved walls without having to cut every block. Trenwyth Industries Inc., Emigsville, Pa., manufactures the concrete masonry units with a variety of decorative surface textures and colors. If the concept catches on, additional producers are probably just around the bend.

|

| UPDATE: This successful ad campaing introduced curved washroom accessories, circa 1993 |

When an architect designs a brick cavity wall, lines are always straight, mortar joints neatly trimmed, and the assembly clearly drawn to show the path water is to take to reach weep holes and drain out of the cavity. Just one problem: It is exceedingly difficult to build a cavity wall without mortar dropping to the bottom of the cavity and plugging the weep holes. Water is then trapped inside the wall, where it can cause damage.

Traditional methods of improving drainage, such as placing pea gravel in the base of the cavity to create a drainage channel, do not always work because mortar droppings can collect on top of the gravel and create a dam. Mortar Net USA Ltd., Highland, Ind., has developed the first product I have seen that addresses this problem in a way that recognizes how masonry walls are really built. The new Mortar Net is made from a plastic mesh that is cut in a dovetail pattern. The pattern collects mortar droppings on its high faces so that its lower faces remain open for drainage.

The invention is simple and elegant in concept, inexpensive, easy to install, and addresses a critical construction need. To my mind, it changes the standard of care required by building designers and contractors. There are no more excuses for clogged weep holes; designing a cavity wall without specifying this or a similar product borders on negligence.

I like the tenor of this

While light from the sun is the environmentally correct choice, an electric lamp is nice to have when the sun doesn’t shine.

Fluorescent lamps consume significantly less energy than most incandescent bulbs, but pose their own environmental risks due to potentially toxic chemicals used in manufacturing. This tradeoff has become easier since last year, when Philips Lighting Co., Somerset, N.J., introduced its Alto lamp technology, which uses less than half of the mercury in average fluorescent lamps.

The technology also offers user benefits. Because of the potential for mercury to leach into the environment, most used fluorescent lamps must be treated as hazardous waste. Alto lamps, however, fall below the Environmental Protection Agency’s criteria for toxic leachate and can be disposed with regular garbage. While the marketing advantage of this is obvious, the driving force behind this new technology was not marketing, but manufacturing’s desire to reduce costs and liability by decreasing the amount of mercury handled in the plant.

I am concerned, however, that this improvement may actually result in an increased potential for mercury poisoning. Is there any threshold of mercury that is “safe” to dump into the environment? I hereby challenge Philips (and competitors) to halve again the level of mercury in its products before the end of the century.

They should have listened to me

Here’s one invention that I let slip away from me. Nearly 35 years ago I worked in the product development department of a metal panel manufacturer. One chilly day, I brushed against the south wall of our research lab and discovered that the dark-painted metal wall panels were warm from the sun.

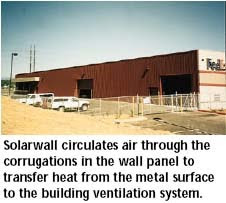

Inspired, I realized that the south walls of many metal-clad buildings could function as giant solar heat collectors. Air could be circulated through the corrugations in the panel and used to transfer heat from the metal surface to the building ventilation system. I sketched out the concept and showed it to the firm’s marketing manager. He appreciated the concept but predicted, quite rightly, that the energy crisis of the 1970s would not last long.

It was a great surprise, then, when I opened a recent mailing from Conserval Systems Inc., Buffalo, N.Y., and found it promoting my idea. Conserval’s Solarwall is patented, trademarked, and developed far beyond my seminal sketches, but is nevertheless my invention.

Do I hear the sound of nervous product managers anxiously dialing their patent attorneys? Or is it just me kicking myself for not commercializing the concept myself?

Have a question you'd like us to answer?

Send an email to michaelchusid@chusid.com

By Michael Chusid

Originally published in Construction Marketing Today, Copyright © 1996